Spotlight on Glass Lyre Press

Tag line: “Exceptional Works to Replenish the Spirit”

Reviewed by Nettie Farris

This is the second in a series from our new Review Editor. Each Spotlight will focus on a different press. Check out the first one!

Interested in distinguishing a publishable manuscript from one that is not? Kelly Cressio-Moeller, Associate Editor for Glass Lyre Press, looks for “poems with emotional anchors, a pulse, a deepening, but also reticence, some mystery—poems that reach further than the page.” She wants poems that make her “see or feel something new in language” she wishes she “had written.” There’s more: “However, a handful of excellent poems does not a manuscript make. Every poem must be strong. Every. Poem.” She wants every nonessential poem gone. Remaining poems must be in the proper sequence: “The ordering is very important, too; there should be cohesion. How does it open? Does it drag in sections? Does a sequence of poems take me out of the reading experience?”

You can see why the most striking aspect of the publications of Glass Lyre Press is coherency. Glass Lyre publishes both chapbooks and full length collections, though full-length collections dominate the catalog. Yes, even these full-length collections form a coherent whole. Submission instructions indicate: “Individual poems must stand on their own merit but complement each other, and work together to present a cohesive and well-ordered manuscript.” A random sampling of the catalog reflects this sense of harmony.

Glass Lyre Press was founded by Ami Kaye in 2013, and originated from an act of compassion. Kaye had established the international journal Perene’s Fountain in January 2008. Readers of this journal have compared the quality of its contents to the quality of a typical anthology. In addition to its other fine writers, Perene’s Fountain has published work by Jane Yolen, Jane Hirshfield, and J.P. Dancing Bear. In 2011, Perene’s Fountain published an anthology, Sunrise from Blue Thunder. The proceeds from this anthology benefitted those affected by the Japan earthquake and tsunami. According to the story, Kaye and her staff, were so smitten with the publication of this anthology, that they began a press, and the press was Glass Lyre.

Ami Kaye, of Indian heritage, was born in Paris and traveled widely with her parents, who exposed her to the arts. While still in elementary school, she began stapling together stacks of paper filled with poetry and prose, adding a painted cover, and calling it a book. Glass Lyre Press is a continuation of this childhood activity, but at an entirely new level. The work of the press is distributed throughout a multi-generational team. It consists of: Mark McKay, Lark Vernon Timmons, Kelly Cressio-Moeller, Elizabeth Nichols, Steven Amussen, Katherine Herschler, Royce Hamel, and Paul S. Kim. Though this staff reflects a global presence, the press largely resides in Chicago, Illinois.

The quality of Glass Lyre’s work speaks for itself. Patricia Caspers, author of In the Belly of the Albatross heard about the press through word of mouth. A fellow poet had read a work in its catalog and suggested “GLP might be a good home for [Casper’s] manuscript.” Caspers refers to the team as “delightful” and praises its members’ patience: “They were all very gracious about letting me take the time to get every word right.” Robert S. King, author of Developing a Photograph of God, expresses a similar sentiment: “Not only is the entire staff a pleasure to work with, but Glass Lyre Press editors want to make sure you’ve done your best and will work with you until you have achieved that goal.” The press is also willing to take a risk on work it finds exceptional, as emphasized by Raymond Gibson, author of Speak, Shade: “Mark McKay and Ami Kaye took a chance on me when no one else would. It’s been both an honor and a privilege to be published by Glass Lyre Press, and to be in such good company.”

The press’s motto is “exceptional works to replenish the spirit.” Kaye emphasizes that “now more than ever we need the arts to help us restore balance and nourish our spirits” and indicates a goal of the press to serve in this restoration. “It is our hope that our books will rejuvenate and restore the spirit, and provide inspiration like meditations people will return to and feel replenished.” In addition, Kaye suggests the practicality of short forms in this endeavor: “Sometimes it is difficult to find time to read a novel, but most people can manage to read a couple of poems or a short fiction piece, and feel replenished or experience a mood lift much in the same way one does in hearing a piece of music.” The following four collections, at least, truly do replenish the spirit.

The chapbook Speak, Shade (2013) by Raymond Gibson is a meditation on the senses and the inadequacy of those senses. Though most of the collection reflects on the five senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell, “Cardinal Senses” alludes to our other, uncounted, senses:

The chapbook Speak, Shade (2013) by Raymond Gibson is a meditation on the senses and the inadequacy of those senses. Though most of the collection reflects on the five senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell, “Cardinal Senses” alludes to our other, uncounted, senses:

This number will not do

What of the senses of movement and time

and lacklove that pain

we fill with which does not answer

to either of five wounds

It is a difficult collection to decipher, much like a koan, but more lyrical than narrative. As we learn from “Blind Timescapes,” the divine / masks the unknown.” Masks occur as a repetitive image. The opening poem, “The Cataracts” ends: “what are the eyes if not complicit / not a glass shield but the holes of a mask.” The visual image of a mask appears on the title page, and the image of the mask is also invoked in “If”: “The way statues are called lifelike and the living statuesque the way life mask and death mask are synonyms.”

In addition to masks, the collection plays on the concepts of dreaming, absence, silence, ghosts, memory, and echoes. It attempts to speak without speaking. “Echo of Light” ends: “yes here is light / though the star’s years dead.”

“Hand in Emptiness” pronounces: “to know loss / is to first know possession.” “Distance” begins: “How describe sight to the blind.” Then later continues:

how explain

to a four-fingered man

absence

without a knuckle or stump

to tell is to amputate the very digit

It’s as if knowledge of a lack makes the lack. And we prey on this lack, with our knowledge of it. “Blind River” ends:

Still they bore sons and whispered that their small age would not see the chaos yet

Cowards sending children ahead of them in the dark

The concept of blindness occurs throughout this collection. “Peregrination” directs our attention:

look a deaf-mute leading the blind by hand

both are neither ghosts nor memories but

ourselves at a dream’s mercy

here in the gateless fence of horn and ivory[.]

And eyelessness. “Sculpture Garden” begins: “The eyeless bust of a god without a mouth” and ends: “none can enter nor see at all.”

Still, within this paradox, within this irony, there is a protest. The list poem “Against Futility” offers solutions, though they seem rather ineffectual; for example, “the ink is clear and dries blank . . . the book not yet felled planted.” And “The Night Shore” concludes:

These are difficult poems indeed, but the journey is worth it.

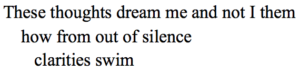

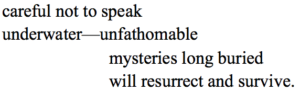

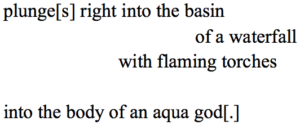

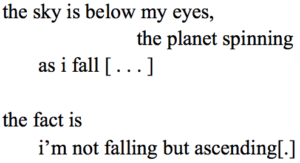

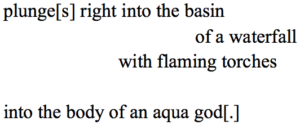

Aquamarine (2014), by the Japanese poet Yoko Danno, is a full-length collection of poems infused with water imagery. Water, in these poems, comes in many forms: pond, river, sea, waterfall, and seems to have magical powers. As we learn from the conclusion of “tell it to the stone”:

Aquamarine (2014), by the Japanese poet Yoko Danno, is a full-length collection of poems infused with water imagery. Water, in these poems, comes in many forms: pond, river, sea, waterfall, and seems to have magical powers. As we learn from the conclusion of “tell it to the stone”:

Water is also often associated with spiritual beings. In “fire meets water,” the speaker of the poem

In “catfish in the woods,” “the giant / fish-god tosses and turns / in the deep ocean bed.” In “water city,” we meet not gods, but angels: “what’s happening below / the glittering surface / of the canal water? dust / falling from smiling angels.”

These are poems of fluid transformations. Within the middle section of “moon appearing,” one dream slides into another:

wade through waves of light

to the place of your birth,

where white flower petals fall

without a breeze, sweeping

into a next dream—a pair

of white tigers appear

in a dewy gardenia bush

flirting with each other[.]

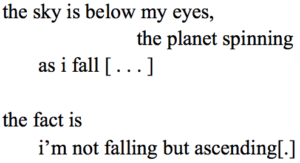

In addition, the closing of this poem reverses the opening. The poem begins: “a dream is just behind the door—, and ends: “it was over / before i knew when / a door was just behind the dream.” A similar reversal takes place in “fire meets water”:

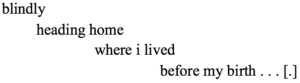

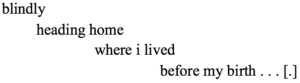

Several poems in the collection play with transformations of time. “narrow pathway” closes: “i am / prepared / for the birth / of my own mother.” “at sea” closes similarly:

Finally, the opening of “eater is eaten” cautions: “if grains / of sand / get / into your / shoes / don’t / look back / your unborn / will get / injured.”

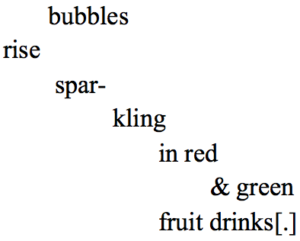

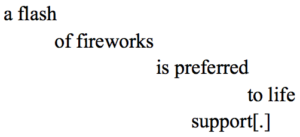

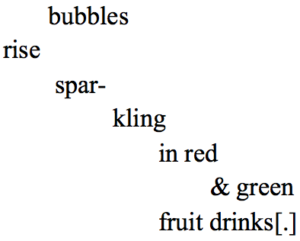

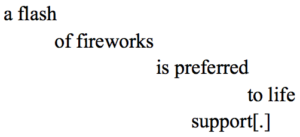

One of the most interesting poems in the collection is “all around, slow death.” The tone of the poem contrasts that of its title:

The poem experiments with the same sort of effervescence in the context of fireworks, blood vessels, a balloon. This repetition suggests that living and dying are, in fact, the same thing. The opening complicates the poem:

Perhaps the poem is demonstrating that life without death is not really life. Nevertheless, this is certainly an example of a title that adds something to the poem.

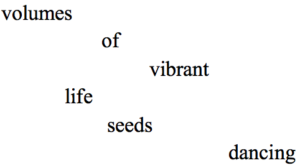

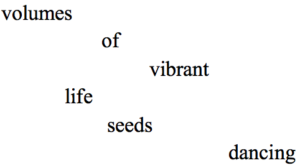

These are poems of continuous motion, poems which, though fluid, and in constant transformation, rely on crisp, clear images that appeal to the senses. “at random” opens:

It’s as though they are enacting the advice of the tea master in “Morning Walk (a poem that associates a morning walk with the Japanese Tea Ceremony): “Perform the ceremony as if you were in a dream, but mind you, let your brains respond vividly to the sound and smell and light in the room, as in meditation.”

As its title suggests, Listening to Tao Yuan Ming (2015), by Dennis Maloney, is a collection of poems about conversation. Conversations across time. Conversations within time. The collection consists of three parts. Part 1, “Twenty Poems After Drinking Wine,” gives us twenty poems translated from the ancient poet Tao Yuan Ming, but stripped to their essence, as the Forward informs us. Part 2 consists of thirteen poems in the form of letters to Tao Yuan Ming. Part 3, “Listening to Tao Yuan Ming,” consists of twenty-three more contemporary poems influenced by Tao Yuan Ming. So the collection, largely, is a conversation through, with, and about this ancient Chinese poet. In addition, many of the individual poems in this collection reference companions, and sharing conversation with these companions, sometimes in the form of poems. The notebook, the writing desk, is ever present.

As its title suggests, Listening to Tao Yuan Ming (2015), by Dennis Maloney, is a collection of poems about conversation. Conversations across time. Conversations within time. The collection consists of three parts. Part 1, “Twenty Poems After Drinking Wine,” gives us twenty poems translated from the ancient poet Tao Yuan Ming, but stripped to their essence, as the Forward informs us. Part 2 consists of thirteen poems in the form of letters to Tao Yuan Ming. Part 3, “Listening to Tao Yuan Ming,” consists of twenty-three more contemporary poems influenced by Tao Yuan Ming. So the collection, largely, is a conversation through, with, and about this ancient Chinese poet. In addition, many of the individual poems in this collection reference companions, and sharing conversation with these companions, sometimes in the form of poems. The notebook, the writing desk, is ever present.

Understandably, for a book grounded in the Taoist tradition, many of these poems are grounded in travel metaphors. Images of roads, paths, and trails abound. Poem #17 in Section One advises: “Traveling on and on, one loses the path— / but trusting the Way, one might get through.” Poem # 19 cautions: “The world’s paths are vast and many, / so decisions are difficult at every crossroad. Poem #20 warns: “Sages flourished long before our time / and few today remember the Way.” “Be Drunk” is more positive: “An invisible wind carries / us through this world / but who says you can’t choose the road”; though still advises prudence: “Don’t be like the traveler / who walks all day / but doesn’t feel / the earth beneath him.”

One follows the Way with others. From “Not Hermits But Householders” we learn about “the heart’s happiness, / at having another / to share this trail.” From “If Tao Yuan Ming Came to Visit,” we learn that the speaker of the poem and the Norwegian poet Olav Hauge “shared a poem or two.” Similar, we learn from “Old Friends from Far Away”:

When I meet an old friend

we catch up on news

and memories

of days gone by,

share strong tea

and new poems.

The most important others sharing our path are teachers. Tao Yuan Ming himself is a teacher shadowing this collection, but the first time we hear explicitly of teachers is in Poem # 11:

One teacher was praised for his compassion,

another as a sage.

One fasted so often he died young,

the other carried hunger all his life.

They left their names in our memory

but at the cost of what suffering?

“One Day We Will Vanish” links the speaker of the poem with teachers; the speaker becomes a teacher: “Roaming through / old books, I join / timeless teachers.” The entire poem “Gratitude to Our Teachers” is dedicated to teachers:

They were the majestic

oaks and maples

in our forest,

teaching us to

write and sing

our own songs

by hearing theirs.

“The Voice of the Bell” makes teachers of our environment, our surroundings:

Scent of damp pine needles,

incense and oranges,

the dance of rain on the roof,

children rolling in the grass,

a sip of tea, a frog

croaking in a nearby pond

as dusk approaches.

These are our teachers,

and we are the petals

unfolding on the flower

that is our world.

Ultimately, this is a collection about aging, and the wisdom that comes from experience. “All Those Nights We Harmonized” contrasts innocence with experience:

Su Tung-po said your

poems were withered

on the outside

but rich within.

That coming of age

reading your poems

was like gnawing

on withered wood.

Reading them after

experience in the world,

it seems that the previous

decisions of our lives

were made in ignorance.

The collection is pulled together by this concern with aging, experience, conversation with teachers across time, and concern with the future. “Crossing the Yangtze” depicts a journey through time rather than space: “We cross the Yangtze / on the new concrete bridge / into tomorrow.”

In the Belly of the Albatross (2015), by Patricia Caspers, is a full-length collection of poems undivided by sections. It tells the story of a journey, not through the familiar belly of a whale, as in the Book of Jonah, but, as the title suggests, through the belly of an albatross. The title poem, “In the Belly of the Albatross,” begins with an epigraph by poet/environmental activist Victoria Sloan Jordan on the demise of the albatross. These birds, when they die, litter the Hawaiian Islands with tons of plastic they have consumed and held contained in their bodies: “A Hawaiian elder counseled us not to view the albatross or the islands as victims of plastic pollution. They have called this problem to them, she said, to deliver us a message. We are hit with this message every day. When can we say we’re receiving it?” The poem equates our own demise to that of the albatross: “Each day we fill our bellies with lack . . . until we are anchored with nothings.” Consequently, we are damaging ourselves, our environment: “Our bodies swell with sorrow, / and the albatross heavies herself / on the bright remnants of our grief.”

In the Belly of the Albatross (2015), by Patricia Caspers, is a full-length collection of poems undivided by sections. It tells the story of a journey, not through the familiar belly of a whale, as in the Book of Jonah, but, as the title suggests, through the belly of an albatross. The title poem, “In the Belly of the Albatross,” begins with an epigraph by poet/environmental activist Victoria Sloan Jordan on the demise of the albatross. These birds, when they die, litter the Hawaiian Islands with tons of plastic they have consumed and held contained in their bodies: “A Hawaiian elder counseled us not to view the albatross or the islands as victims of plastic pollution. They have called this problem to them, she said, to deliver us a message. We are hit with this message every day. When can we say we’re receiving it?” The poem equates our own demise to that of the albatross: “Each day we fill our bellies with lack . . . until we are anchored with nothings.” Consequently, we are damaging ourselves, our environment: “Our bodies swell with sorrow, / and the albatross heavies herself / on the bright remnants of our grief.”

Much of the collection concerns itself with grief (the entire poem of “The Five Stages of Grief,” for example). though it is primarily the grief of females, females throughout history. As we learn from “ Hatsuhana Beneath the Waterfall,” based on a Japanese legend, Hatsuhana, the speaker of the poem “was a wagyu bride, sold / like prized beef.” There is a contrast between inner reality and outer appearance:

Under the harsh wrath of water,

there was silence, and I prayed

for one hundred days.

Such a good wife, the villagers said.

Izanami-no-kami, I begged, you too

know a wife’s grief. Please, wash this poison

from my breast.

Females in this collection find themselves imprisoned within tight situations. Nana, in “Nana Ivy’s Royal Typewriter,” types: “DON’T FENCE ME IN.” “Baby Catcher” is in the voice of the (eventually) freed slave, Bridget Mason, who informs us of the advice of her mother: “When you’re tall as the corn, she said, / he’s gonna come for you. Don’t fight him.” “The Squeeze Inn” tells the story of a woman who has a one-night stand with her ex-husband. At the time, she is sort of in between two men, both losers. The evening begins:

You didn’t have to get all

gussied up for me, he said,

and I smacked him between

those blue eyes with a rubber glove.

And ends:

I watched him sleep and realized,

all our knotted, married nights

this is where he lay, another woman

awake in his warmth, wondering

at the gold band on his wedding finger.

I’d never left a room so silently.

Some of these females have dreams of freedom. The speaker of “What Mama Said,” announces: “I told Mama I got dream wings. / She said you must be a ostrich, Girl. / You ain’t flying’ nowhere.” “Irene’s Goodbye,” from the point of view of a woman in a nursing home, displays a more positive perspective. She introduces her nurse: “she thinks / I’m some pansyfaced girl with pigtails / gotta learn to mind her manners—.” However, the speaker has plans of her own: “I wanna cozy down in the deep pocket / of some small town lounge . . . palm myself a glass full of fire / while the pool balls smackthud . . . Hell if I ain’t gonna roll me there.” The voice of “Unreported,” a poem in three parts, is the most aggressive voice in the collection. In section two (“The Woman I Intend to Be”) we hear:

Who am I kidding?

I am no goddess. There is no spring

to beckon me from the underworld.

That boy has long since forgotten

my name.

And in section three (“The Mother I am: An Open Letter to Demeter”) we learn: “The time for prayer has passed. / Gather the wronged . . .

we will not stop gathering the arsenal of our rage,

will not stop until we storm the fortress,

tear it down stone by stick, blaze the pyre,

and watch as every last fucker burns.

The voice of these poems is essentially female, concerned with motherhood, daughters, the place of women within the society of men. Images of water (contrasted with drought) abound (bath water, baptismal water), as do references to the moon. “Ekphrasis: 36 Ghosts, No. 5” introduces both these images: “It was my old friend, Moon / and my wise rival, Water.” In addition, the collection references messages, “seers and shamans,” prayers and invocations. The collection opens with “Oracle,” about an oracle, who, ironically, doesn’t seem much of an oracle: “What if an oracle lived at the end of your street / in a wonky red house with yellow trim.” (Nevertheless, we must attend to these symptoms of the planet. The symptoms of women, of immigrants, of wildlife. The underclass.) The collection ends with “Piece by Piece”: “Tear apart the cosmos. Let there be a new kind of light.” In the Belly of the Albatross is a beautiful work of ecofeminism.

Glass Lyre Press publishes approximately eight works a year. Typically, the press attends the AWP (Associated Writing Program) Conference & Bookfair (“the nation’s largest marketplace for independent literary presses”) and is known for its use of social media (largely Facebook and Twitter). The press is currently soliciting work for its latest anthology, Collateral Damage, which will benefit victimized children. Glass Lyre publishes both benefit anthologies and anthologies of works published in Pirene’s Fountain. The Aeolian Harp Series includes anthologies of folios of up to six pages per poet. The press awards two prizes annually: The Kithara Book Prize and the Lyrebird Award. Submissions are open January through February and September through October.

Beate Sigriddaughter

Beate Sigriddaughter  Alexis Groulx’s

Alexis Groulx’s

The chapbook Speak, Shade (2013) by Raymond Gibson is a meditation on the senses and the inadequacy of those senses. Though most of the collection reflects on the five senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell, “Cardinal Senses” alludes to our other, uncounted, senses:

The chapbook Speak, Shade (2013) by Raymond Gibson is a meditation on the senses and the inadequacy of those senses. Though most of the collection reflects on the five senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell, “Cardinal Senses” alludes to our other, uncounted, senses:

Aquamarine (2014), by the Japanese poet Yoko Danno, is a full-length collection of poems infused with water imagery. Water, in these poems, comes in many forms: pond, river, sea, waterfall, and seems to have magical powers. As we learn from the conclusion of “tell it to the stone”:

Aquamarine (2014), by the Japanese poet Yoko Danno, is a full-length collection of poems infused with water imagery. Water, in these poems, comes in many forms: pond, river, sea, waterfall, and seems to have magical powers. As we learn from the conclusion of “tell it to the stone”:

As its title suggests, Listening to Tao Yuan Ming (2015), by Dennis Maloney, is a collection of poems about conversation. Conversations across time. Conversations within time. The collection consists of three parts. Part 1, “Twenty Poems After Drinking Wine,” gives us twenty poems translated from the ancient poet Tao Yuan Ming, but stripped to their essence, as the Forward informs us. Part 2 consists of thirteen poems in the form of letters to Tao Yuan Ming. Part 3, “Listening to Tao Yuan Ming,” consists of twenty-three more contemporary poems influenced by Tao Yuan Ming. So the collection, largely, is a conversation through, with, and about this ancient Chinese poet. In addition, many of the individual poems in this collection reference companions, and sharing conversation with these companions, sometimes in the form of poems. The notebook, the writing desk, is ever present.

As its title suggests, Listening to Tao Yuan Ming (2015), by Dennis Maloney, is a collection of poems about conversation. Conversations across time. Conversations within time. The collection consists of three parts. Part 1, “Twenty Poems After Drinking Wine,” gives us twenty poems translated from the ancient poet Tao Yuan Ming, but stripped to their essence, as the Forward informs us. Part 2 consists of thirteen poems in the form of letters to Tao Yuan Ming. Part 3, “Listening to Tao Yuan Ming,” consists of twenty-three more contemporary poems influenced by Tao Yuan Ming. So the collection, largely, is a conversation through, with, and about this ancient Chinese poet. In addition, many of the individual poems in this collection reference companions, and sharing conversation with these companions, sometimes in the form of poems. The notebook, the writing desk, is ever present. In the Belly of the Albatross (2015), by Patricia Caspers, is a full-length collection of poems undivided by sections. It tells the story of a journey, not through the familiar belly of a whale, as in the Book of Jonah, but, as the title suggests, through the belly of an albatross. The title poem, “In the Belly of the Albatross,” begins with an epigraph by poet/environmental activist Victoria Sloan Jordan on the demise of the albatross. These birds, when they die, litter the Hawaiian Islands with tons of plastic they have consumed and held contained in their bodies: “A Hawaiian elder counseled us not to view the albatross or the islands as victims of plastic pollution. They have called this problem to them, she said, to deliver us a message. We are hit with this message every day. When can we say we’re receiving it?” The poem equates our own demise to that of the albatross: “Each day we fill our bellies with lack . . . until we are anchored with nothings.” Consequently, we are damaging ourselves, our environment: “Our bodies swell with sorrow, / and the albatross heavies herself / on the bright remnants of our grief.”

In the Belly of the Albatross (2015), by Patricia Caspers, is a full-length collection of poems undivided by sections. It tells the story of a journey, not through the familiar belly of a whale, as in the Book of Jonah, but, as the title suggests, through the belly of an albatross. The title poem, “In the Belly of the Albatross,” begins with an epigraph by poet/environmental activist Victoria Sloan Jordan on the demise of the albatross. These birds, when they die, litter the Hawaiian Islands with tons of plastic they have consumed and held contained in their bodies: “A Hawaiian elder counseled us not to view the albatross or the islands as victims of plastic pollution. They have called this problem to them, she said, to deliver us a message. We are hit with this message every day. When can we say we’re receiving it?” The poem equates our own demise to that of the albatross: “Each day we fill our bellies with lack . . . until we are anchored with nothings.” Consequently, we are damaging ourselves, our environment: “Our bodies swell with sorrow, / and the albatross heavies herself / on the bright remnants of our grief.”

M. L. Brown

M. L. Brown

stephanie roberts

stephanie roberts Ivonne Gordon Carrera

Ivonne Gordon Carrera

Crixa, by Megan Hudgins, won the inaugural chapbook contest in 2014. It is a small collection of poems that addresses big subjects. These poems are about life and death. These poems are primal. How fitting that the collection centers on the image of rabbits, which we associate with fecundity. The collection’s title is borrowed from the novel Watership Down by Richard Adams. The word crixa, a lapine word from this novel, refers to “the center of the Efrafa warren” the warren from which females are recruited in order to ensure survival at the new warren Watership Down. In effect, the title refers to a sort of spring, or well, of fertility (or at least the possibility of fertility).

Crixa, by Megan Hudgins, won the inaugural chapbook contest in 2014. It is a small collection of poems that addresses big subjects. These poems are about life and death. These poems are primal. How fitting that the collection centers on the image of rabbits, which we associate with fecundity. The collection’s title is borrowed from the novel Watership Down by Richard Adams. The word crixa, a lapine word from this novel, refers to “the center of the Efrafa warren” the warren from which females are recruited in order to ensure survival at the new warren Watership Down. In effect, the title refers to a sort of spring, or well, of fertility (or at least the possibility of fertility).

The Girl with the Jake Tattoo, by Gary Leising (2015), is a collection of loose narrative poems (you never know how they will end, or how they will turn in getting there). These poems, set against a backdrop of figures from history and popular culture play with the looseness of identity. These poems are about transformation. These poems are about fluidity. As we hear in “Pentimenti”: “If it wasn’t / for the frames, I wouldn’t know where art / ends and where life begins.”

The Girl with the Jake Tattoo, by Gary Leising (2015), is a collection of loose narrative poems (you never know how they will end, or how they will turn in getting there). These poems, set against a backdrop of figures from history and popular culture play with the looseness of identity. These poems are about transformation. These poems are about fluidity. As we hear in “Pentimenti”: “If it wasn’t / for the frames, I wouldn’t know where art / ends and where life begins.” Winner of the 2015 chapbook contest, An Animal I Can’t Name, by Raegen Pietrucha, is, a collection that explores naming. In contrast to feminist theorists, who have historically argued about the power of naming (and the subject who names), these poems suggest its difficulty as well as its futility. The collection’s title comes from “The Ranch in California,” which appears toward the end of the book. The speaker of this poem lies beneath a man, while “clouds above unravel / sky like hides ripped, revealing red / tissue of an animal I can’t name.” This is a poem (this is a collection) about secrets.

Winner of the 2015 chapbook contest, An Animal I Can’t Name, by Raegen Pietrucha, is, a collection that explores naming. In contrast to feminist theorists, who have historically argued about the power of naming (and the subject who names), these poems suggest its difficulty as well as its futility. The collection’s title comes from “The Ranch in California,” which appears toward the end of the book. The speaker of this poem lies beneath a man, while “clouds above unravel / sky like hides ripped, revealing red / tissue of an animal I can’t name.” This is a poem (this is a collection) about secrets. Christopher McCurry’s Nearly Perfect Photograph: Marriage Sonnets is a collection unified in both form and theme. It consists of 18 contemporary non rhyming sonnets, a sequence of unsentimental realist lyrics. These are no Sonnets from the Portuguese. Their tone might be described as hard-boiled. Imagine Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, married, and with children. However, the crimes he investigates occur in his own home. The settings in these poems are most often bedroom, bathroom, kitchen. Dominant images are of sex and domesticity. The speaker clearly prioritizes sex rather than domesticity.

Christopher McCurry’s Nearly Perfect Photograph: Marriage Sonnets is a collection unified in both form and theme. It consists of 18 contemporary non rhyming sonnets, a sequence of unsentimental realist lyrics. These are no Sonnets from the Portuguese. Their tone might be described as hard-boiled. Imagine Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, married, and with children. However, the crimes he investigates occur in his own home. The settings in these poems are most often bedroom, bathroom, kitchen. Dominant images are of sex and domesticity. The speaker clearly prioritizes sex rather than domesticity.

Lynn Marie Houston’s

Lynn Marie Houston’s Hillary Kobernick

Hillary Kobernick Kendall Pakula

Kendall Pakula